The Media and the War on Terrorism

These candid conversations capture the difficulties of reporting during crisis and war, particularly the tension between government and the press. The participants include distinguished journalists - American and foreign, print and broadcast - and prominent public officials, past and present. They illuminate the struggle to balance freedom of the press and the right to know with the need to protect sensitive information in the national interest. As the Information Age collides with the War on...

Search in google:

These candid conversations capture the difficulties of reporting during crisis and war, particularly the tension between government and the press. The participants include distinguished journalists American and foreign, print and broadcast and prominent public officials, past and present. They illuminate the struggle to balance free speech and the right to know with the need to protect sensitive information in the national interest. As the Information Age collides with the War on Terrorism, that challenge becomes even more critical and daunting.

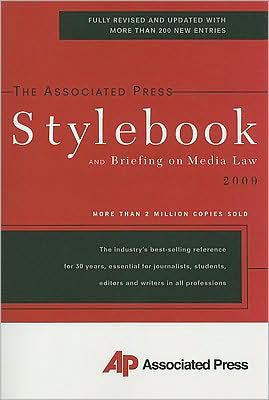

The Media and the War on Terrorism\ \ Brookings Institution Press\ Copyright © 2003 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUITON\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 0-8157-3581-2 \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ Introduction \ For a generation, until the collapse of the Soviet Union, American news organizations reported on the world largely through the prism of the cold war. Particularly on the TV networks' evening news programs, where stories have to be short and preferably dramatic, the East-West conflict was a useful framing device. Moreover, the epicenter of the struggle was in Europe, the part of the world that most Americans care most about and whose cultures American journalists were more apt to understand and whose languages they were more apt to speak. But after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, international news seemed to lose its urgency for many Americans. Media enterprises turned their attention to domestic matters, which were of greater interest to their consumers. News businesses were not displeased to shut down expensive foreign bureaus. At the same time, without the threat of a rival superpower, U.S. foreign policy makers searched for new defining themes. Revolving attention turned to such topics as human rights, trade, the environment, and regional hot spots; when necessary, news organizations simply parachuted journalists into war zones or other disaster areas. Although the Associated Press, CNN, and a handful of major newspapers-notably the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and Wall Street Journal-continued to maintain a substantial presence abroad, by the morning of September 11, 2001, the world outside the United States had become of only modest interest to the rest of the American journalism establishment. That day's horrendous events instantly created a new focus of American national purpose, forcefully articulated by the president, and a new framing device for the media: The War on Terrorism.\ What was most immediately apparent about covering this war was its breadth, the vast scope of what had to be included. Take coverage between January 1 and April 5, 2002, on the ABC, CBS, and NBC nightly news. While there were strong competing stories, such as the Enron scandal and the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, 28 percent of total stories still related to terrorism. There were accounts of the battle of Gardez in the eastern mountains of Afghanistan, Israeli-Palestinian violence intensifying in the Jenin refugee camp, airport security testing, the kidnapping of Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl in Pakistan, a crackdown on terrorism in Yemen, legal charges against John Walker Lindh and Zacarias Moussaoui, feature stories on how people were coping, and business stories about the impact on the stock market. It was a foreign story and a domestic story. It was a military story, of course, but also a diplomatic and economic story. Coverage of the anthrax scare encompassed health and science. The creation of the Department of Homeland Security was to be a major story about governance and politics.\ A complementary impression was the complexity of the circumstances that the United States had been thrust into: a worldwide terrorist network of al Qaeda operatives; the tragedy of Afghanistan; the conflict between Pakistan and India over Kashmir; Russia's President Putin and his war in Chechnya; the aftershocks of the terrorist attacks in the U.S. that would be felt in East Africa, Indonesia, and the Philippines; the unresolved crisis of Palestine; an unfinished agenda in Iraq. All related. And always at root was the need for knowledge of Islamic culture and the Muslim religion, which generally had not been of interest to most Americans. A simple fact: in a 1992 survey of 774 foreign correspondents working for U.S. news organizations, only ten said that they could conduct an interview in Arabic.\ To explore a conflict "unusually complex both to wage and to report," in the words of former Brookings president Michael Armacost, the Brookings Institution joined with Harvard University's Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics, and Public Policy to create the Brookings/Harvard Forum on the Role of the Media in the War on Terrorism. There were twenty sessions-from October 31, 2001, to September 19, 2002, essentially spanning the first year of the war-made up of informal conversations among past and present government officials, foreign and domestic journalists, and scholars. This book of edited transcripts tries to capture the flavor of their discussions.\ The book is arranged in six sections. The first, "The Media and the Government: World War II to the End of the Twentieth Century," includes four panel discussions that look back on past crises. In the first discussion, journalists and the spokesman for the U.S. embassy in Saigon during the Vietnam War review press coverage of conflicts from World War II through the 1991 Persian Gulf war. They reflect on changes in technology, changes in the government's attitude toward the press, and economic changes that affect their work. In the second, four former presidential press secretaries explain how they handled national security questions at the White House. Was it ever appropriate to withhold information from the media? Or to leak information to favored reporters? In the third, a former secretary of defense, a former CIA director, and a former U.S. representative to the United Nations remember the media as an obstacle to getting their jobs done, yet in the fourth discussion, a former secretary of state tells how he used the media to promote policies he favored. The press, as seen by high-ranking government officials: obstacle or opportunity? And to what extent was the so-called CNN effect-the impact of instantaneous, worldwide TV coverage-responsible for President George H. W. Bush's decision to send American troops to Somalia in 1992 and President Clinton's decision to withdraw them the next year?\ Relations between the Pentagon and the press during the early stages of the war in Afghanistan is the subject of the second section, "War in Afghanistan: The Early Stages." At a November 2001 meeting at Brookings between Washington news bureau chiefs and top Defense Department information officers, the journalists outlined their needs for information and access and the information officers let them know how much the department was willing to provide. Another panel of media critics offered a three-month assessment of the Pentagon's press policies in January 2002. Could the government have been more cooperative in providing reporters with information and access? All agreed that geography and security concerns in Afghanistan made the operation particularly difficult to cover, yet wasn't the problem, one journalist argued, that the press and the government have conflicting institutional positions that cannot be reconciled?\ In section three, "The Journalist's Dilemma: Three Stories," the panels turn to the media's coverage of-or disinterest in-three terrorism-related stories to look for clues to why some things that are important (at least in retrospect) do not get much attention. A report by the blue-ribbon Hart-Rudman Commission predicted events much like those that occurred on 9/11, but it was barely noticed when it came out in January 2001. Was that because of competition from other newsmaking events, or was the report too scary, or was it not promoted sufficiently by the commission? The anthrax scare, on the other hand, got plenty of attention. The media's problems lay in deciding what to report in the absence of hard evidence, dealing with scientific uncertainty, and striking the proper balance between being necessarily informative and need-lessly frightening. The third story concerned dissent. In the months following 9/11 there was wide support for the antiterrorism campaign and very few stories about dissent. How much attention should the media pay to dissent when it is a marginal aspect of the national mood? These are the daily dilemmas of journalism.\ News gathering in Afghanistan, the Middle East, and Washington is the focus of section four, "Reporting from the Field: Three Sites." In the first discussion, journalists who had just returned from Afghanistan explain the new technologies of war coverage and techniques for surviving in a war in which journalists often were targets. Their vastly different experiences range from being caught in the crossfire of competing Afghan warlords at Tora Bora to being tightly controlled by the U.S. military at Kandahar airport. How do war correspondents assess personal risk? In the second discussion, correspondents covering the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians also touch on reporting in a dangerous environment, but they focus more on sorting truth from propaganda, changes in a conflict with a long history, differences between American and European reporting, and the problems in covering shuttle diplomacy. The third conversation, about news gathering in Washington, takes place among foreign correspondents, who explain the news angles that are especially important to their audience; relations with their editors, who often get breaking news from the United States before they do, through the Internet; their treatment by the U.S. government; and how they deal with their audiences' stereotypes of Americans.\ "From Different Perspectives," section five, includes a discussion of the U.S. government's public diplomacy program and whether it differs from propaganda, an assessment of the role of Congress in the campaign against terrorism, an analysis of American public opinion during 2001-02, and the perspectives of four Americans with distinguished careers in public service who were asked to place the war on terrorism and the government's response in a broader context.\ The book concludes with section six, "9/11 and Beyond," in which a panel of journalists returns to the beginning, to the remarkable story of how American news organizations covered the events of September 11, 2001. The panelists review relations between the government and the media in the first year of the war on terrorism, and they turn finally to the factors that may account for the dramatic rise and fall in public support for the media that occurred over the year.\ Here is an opportunity to eavesdrop on interesting conversations among men and women who have had unique experiences. There is new information-and good stories. The notes to this introduction are meant to constitute a selective bibliography for those who wish to delve deeper into the topics in each section. Certain currents or themes keep popping up, and they are worth further attention.\ Technology: Journalism and War Respond to Change\ What becomes clear from the first comment in the first panel discussion is how aware journalists are of how changes in technology have affected their work. Daniel Schorr begins by explaining the technology of radio reporting from Omaha Beach on D-Day in 1944, and Ted Koppel joins in: "Let me pick up where Dan Schorr left off, because there is kind of an evolutionary scale here in terms of the technology and how the technology has had an impact on the way that things are covered." He compares TV coverage in Vietnam in 1967, when "as much as three days might elapse between the time that the story was written and the time it got on the air," and today, when "a journalist has to be prepared to go on the air instantly, around the clock." For the audience, that means knowing about events sooner; for Koppel, it also means less time for correspondents to think about and report the events.\ Those responsible for government information policy feel the same pressures. Describing what she called "one new dynamic of warfighting and war reporting in the Information Age," Victoria Clarke, the Pentagon's chief spokesperson, has written, "We can be quick, or we can be accurate, but [it] is a challenge to be both at the same time. With news hitting the airwaves or Internet almost as quickly as it happens, journalists are understandably impatient for information. Our challenge is to find a balance between speed and precision-being as quick as we can and as accurate as possible."\ The battlefield uses of new technologies-such as small, inexpensive digital video cameras-suggest not only improved ways to relay copy from inaccessible places, but, in the constant tug between military authorities and journalists, the possibility of military field commanders losing control of the story. Michael Gordon of the New York Times explains how using new technologies affected his reporting from Afghanistan: "I had no relationship with the American military, despite repeated efforts to establish one. But what I did have was my sat phone, and I had e-mail, and I could kind of call back to the Pentagon and say, 'Look, this is what I see here. How does it fit with what's supposedly happening?'"\ And yet in war today there is another type of technology that also may have a profound impact on what is reported and how. Increasingly military technology, the new tools of war, determines how basic information is provided and authenticated. That began to become apparent in 1991 during the Persian Gulf war, when the world learned of bombs hitting Iraqi targets from U.S. military videotapes presented before an audience of journalists playing the part of "extras" in the drama, asking questions that TV viewers often found irritating. The military clearly set out to dominate the news, and it had the equipment to succeed.\ Pentagon briefings, often technologically enhanced, reached an apex under Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld during the fighting in Afghanistan. As reported in the Washington Post on December 12, 2001: "The Rummy Show has aired two or three times a week since bombs-away on Oct. 7, and it's a direct hit. The best zingers make the nightly news and next day's paper. Members of the public call the Pentagon to find out when Rumsfeld-whose friends call him Rummy-will be on television next. Nielsen Media Research figures that something like 800,000 people watch his appearances live on cable." Note how often conversations in this book turn to Rumsfeld's briefings-sometimes in awe, as when German TV correspondent Claus Kleber reported on the reaction in his country, and sometimes in frustration, as when ABC correspondent John McWethy said of the briefings: "Message control is the way that this administration is trying to communicate what it is trying to do." In short, the government's briefing system is designed to give the public the information that the government wants the public to have, but it is not necessarily designed to meet the demands of the press.\ At the same time, the advent of two technological innovations-cable TV with its twenty-four-hour news channels and complicated military weaponry that requires explanation-has produced a new breed of semi-journalists: a corps of retired generals and admirals and other experts whose pointers have been much in evidence on TV screens since the 1991 Persian Gulf war.\ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from The Media and the War on Terrorism Copyright ©2003 by THE BROOKINGS INSTITUITON. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Foreward1Introduction1Pt. 1The Media and the Government: World War II to the End of the Twentieth Century152Lessons of Wars Past173Presidential Press Secretaries304National Security Decisionmakers475The CNN Effect63Pt. 2War in Afghanistan: The Early Stages836The Pentagon and the Press857Three Months Later95Pt. 3The Journalist's Dilemma: Three Stories1118The Hart-Rudman Commission Report1139The Anthrax Attacks and Bioterrorism12410Dissent145Pt. 4Reporting from the Field: Three Sites16111Afghanistan16312The Middle East18313Foreign Correspondents in Washington198Pt. 5From Different Perspectives22114Public Diplomacy or Propaganda?22315Congress23716Public Opinion25017Overview263Pt. 69/11 and Beyond27318Running toward Danger275Index297