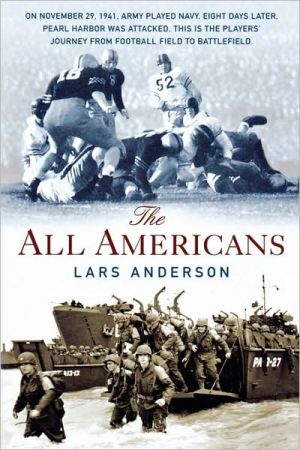

The All Americans

On November 29, 1941, Army played Navy in front of 100,000 fans. Eight days later, the Japanese attacked and the young men who battled each other in that historic game were forced to fight a very different enemy. Author Lars Anderson follows four players—two from Annapolis and two from West Point—in this epic true story.\ Bill Busik. Growing up in Pasadena, California, Busik was best friends with a young black man named Jackie, who in 1947 would make Major League Baseball history. Busik would...

Search in google:

On November 29, 1941 Army Played Navy in Front of 98,942 fans. Eight days later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. This is the story of the players' journey from the football field to the battle field Kirkus Reviews Are we running out of WWII stories? Certainly some of the premises are getting a little thin, and this is a case in point. The setup is just right for Sports Illustrated reporter Anderson (The Proving Ground, 2001, etc.): On November 29, 1941, the Army-Navy game proved to be one of the most thrilling matches ever waged between Annapolis and West Point, with 100,000 spectators (including Eleanor Roosevelt) in the stands. By the end of the game, writes Anderson, "the undermanned Cadet players had fought as hard as Vikings, but the Midshipmen prevailed 14-6." Nine days later the US was at war with the Axis, and Anderson's Rockwellian evocations of prewar military life ("Just the name of the naval academy sounded glamorous to him; it conveyed some magical faraway place where everyone was smart and strong") give way to the hard realities of combat in episodes starring four of the game's players, now commissioned officers. Anderson's account of the game itself is first-class, and the lessons to be drawn vis-a-vis football and war will be familiar to anyone who's been inside a locker room: "We were officers in the war," one officer recalls, "but really, we were just kids in our early twenties. But most of us were put in charge of hundreds of soldiers. It's much easier to deal with that kind of responsibility once you've had the experience of playing football in front of 100,000 people." Anderson's war tales are pretty well done, too, though there's a been-there-done-that quality that will make some readers wish he had done a Seabiscuit and stuck to the game and others of its kind during the war years-as he notes, and most interestingly, the 1944 bout alone raised $58 million in war bonds, whilefor other reasons "never in the history of the Army-Navy game had the two service academies played each other with so much on the line." Surely enjoyable for a readership among academy grads and fans of sports history. Of less service as a window onto WWII. Agent: Scott Waxman/Scott Waxman Agency

CHAPTER ONE\ D-DAY\ The young man stood on the deck of the U.S.S. "Garfield," looking across the English Channel, into darkness. It was just after midnight on June 6, 1944, and the defining hour of Henry Romanek's life was at hand. The "Garfield," a transport ship, had just left the coast of England and was motoring south across the channel, its destination the waters off northern France, about ten miles outside of a quiet, enchanting beach the Allies called Omaha.\ As Romanek gazed onto the black horizon, a cold wind dusting his cheeks, beams of moonlight filtered though the clouds to reveal an armada of ships so vast that it took his breath away. Over five thousand vessels were plowing through the whitecaps, the column of ships stretching as far as Romanek's eyes could see to the east and the west. The day of reckoning, D-day, had arrived. "Good God," Romanek said softly to himself, "Lord, have mercy on us."\ The twenty-four-year-old Romanek was a platoon leader in the 149th Engineer Combat Battalion. Like all the soldiers in his company, he was dressed for battle. He wore a steel combat helmet that was outfitted with a fabric interlining. A life belt (a flotation device) was wrapped snugly around his waist. His first layer of clothing was a wool undershirt, underwear, and thick wool combat socks. On top of that were protective leggings, wool pants, a flannel shirt, an olive drab jacket, and waterproof jumpshoes. He also carried a field bag on his back that held a pancho, toilet articles, a towel, canned food, and a knife, fork, and spoon. A loaded carbine hung over his shoulder, and his dog tags dangled from his neck. On the ring finger of his left hand was his graduation ring from West Point, his dearest possession.\ Romanek had received the ring a year earlier, and now as he looked down on it, the black onyx stone glittered in the moonlight. Romanek was in charge of a platoon of forty-five men, and they were constantly asking him to tell stories from his days at the military academy, especially what it was like to be an Army football player. Romanek had been a two-way standout at the Point in 1941 and '42, playing tackle on both offense and defense. The game he was most often questioned about was the '41 Army-Navy contest, which was played before 98,942 screaming fans at Philadelphia's Municipal Stadium. As Romanek drew closer to what he knew would be the bloodiest fight of his life, that game was still alive in his mind, its details burned into his memory. He must have told his men about that Army-Navy clash a hundred times, maybe more.\ Though three and half years had passed since he last donned an Army football uniform, Romanek still looked like the strapping star he was. Barrel-chested and long-armed, Romanek, at 6'2", 195 pounds, was more toned than muscular. He didn't seem to have an ounce of fat on his tight frame. He had a fair complexion, sleepy blue eyes, caramel-colored hair that was in a crew cut, and a soft, gentle smile that made ladies blush whenever he looked their way. He was, by all accounts, a dashing figure, the kind of clean-cut, riveting young man that people turned to stare at whenever he strolled into a room.\ Yet the boys in his platoon and to Romanek, they were "boys," as most of them were still teenagers—looked up to Romanek not because of his handsome looks but because he was their leader. Romanek thought of his men as an extension of his own family, and he worried and fretted about them probably more than he should have. He spent every night after training reading all their V-mail letters that they were sending to loved ones back home. Because Romanek was the official censor in charge of screening all outgoing U.S. mail for his platoon, he came to know all of his men's deepest secrets and greatest fears. He talked to the men in his platoon about everything, from how they missed their sweethearts back home to the art of making a proper block on the football field. Even when Romanek was agitated, he rarely raised his voice when speaking with his men. Instead, in a firm and steady tone, he would simply lay out what needed to be done and how it would be accomplished. Then he always ended by saying how much he trusted everyone and how they should treat each other like they were blood brothers.\ Romanek's soldiers were from the Midwest, mostly raised on farms and in small towns in Iowa, Missouri, and Nebraska, and they were as gritty as any soldiers Romanek had ever been around. Romanek cared deeply for them, which made him vulnerable on this early morning: Romanek knew that many of them wouldn't survive the coming day. "If all the soldiers on our side are as good as you guys," Romanek told his men a few days before the invasion, "the Germans don't have a chance."\ Along with the rest of his battalion, Romanek and his men had sailed out of New York harbor on the early morning of December 29, 1943 and had spent the better part of six months on the south coast of England preparing for the invasion. The 149th practiced everything from landing on beaches to laying live mines to booby-trapping houses with explosives. The combat engineers had perhaps the most complex mission of any on D-day. They would be among the first to hit the beaches, and they were assigned multiple tasks. They were to identify and blow up any beach obstacle—most were large pieces of steel rail—that would interfere with the landing of troops as the tide began to rise. Then, as quickly as possible, they were to set up signs that would act as guideposts for incoming landing craft. Finally, if they were still alive, they were to clear roads from the beach and set up supply dumps.\ Romanek had gone over the mission dozens of times with his men. He explained to them that the first assault waves on D-day were going to be DD tanks ("duplex drive" tanks that were modified M4 Sherman tanks, which could travel on water as well as land). These tanks would be rigged with rubber devices so—the hope was—they would float. The tanks would be followed by a wave of infantry and engineers. Romanek's engineering platoon was married to the 116th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Infantry Division. They would ride into Omaha Beach together on landing craft, and they would be among the first of the forty thousand men scheduled to land on Omaha, a beach that was about six miles long and slight crescent-shaped. Romanek reminded his men over and over that what they really had to focus on was erecting the large marking panels for the D-3 exit so that subsequent landing craft would know where to go.\ Now on the "Garfield," the landings at Omaha just hours away, Romanek told his platoon to gather around him. When Romanek looked at his men, their eyes seemed to glow like full moons—wide-open and bursting with anticipation. "Now is our opportunity to participate in the greatest armada ever launched in history," Romanek said above the drone of the "Garfield's" engines. "And history will be made by what we do here today. Now let's do our jobs and make our country proud." There were no replies from any of Romanek's men. They merely stared at their leader in silence.\ At around two in the morning, when the "Garfield" was about twelve miles off the coast of France, the order was sounded; "Now hear this! All assault troops report to your debarkation areas."\ Romanek made his way to the spot where he would descend onto a LCM (Landing Craft, f0 Mechanized) that would ferry half of his platoon—approximately twenty-three men—and about eighty infantry personnel to the beach. Along with the hundred or so men on the LCM, there would also be explosive devices and marking panels on board, which Romanek and his platoon of engineers would erect. The marking panels were stored in twenty-foot-long polelike casings. The markers were large triangles that would be staked into the sand and would signify the D-3 exit at Les Moulins, an area on the beach that included a road that led inland to St. Laurent—a D-day objective for the infantry. Romanek carried one of the cases with him as he walked to the disembarkation point.\ Boarding the LCMs was treacherous. The small vessels had already been lowered into the water and they were now bobbing up and down in the ten-foot swells. The men threw a rope net over the side of the "Garfield." In a firm tone, Romanek told his men to go, to climb down the net and then jump into their LCM. "This won't he easy," Romanek said as men began to descend. "Don't lose your grip." Because the engineers were loaded down with weapons, ammo, rations, and a life preserver, mobility was limited. At the disembarking point, one of the men turned to Romanek. His face was white and he was so cold with fear he could hardly move. "Sir, I'm scared," he told Romanek.\ Copyright (c) 2004 by Lars Anderson

\ From the Publisher"In this illuminating book, the author retraces Romanek's life and that of three other Army-Navy players as they evolve from young college men into furious, determined fighters facing trauma, suspense, and loss." —-Reader's Digest (editors's choice)\ "Anderson, a Sports Illustrated staff writer whose father served in the Navy, makes a convincing case that the Army-Navy football rivalry played a significant role in preparing many young men for war...irresistible." —-Sports Illustrated\ "Anderson does a stellar job of portraying life just before and during World War II at the service academies, places of purpose and distinction." —-The Philadelphia Inquirer\ "The appeal of this great story should transcend generational boundaries." —-Boston Herald\ "A compelling, heartfelt drama about the loss of innocence of a generation at war and on the football fields in another time in America. This is a fascinating look at WWII from a completely new point of view."\ —-Doug Stanton, New York Times bestselling author of In Harm's Way\ "With dramatic writing, fully developed characters, and a story that captures both mind and heart, this book is everything the movie Pearl Harbor wanted to be, but wasn't." —- Booklist\ \ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAre we running out of WWII stories? Certainly some of the premises are getting a little thin, and this is a case in point. The setup is just right for Sports Illustrated reporter Anderson (The Proving Ground, 2001, etc.): On November 29, 1941, the Army-Navy game proved to be one of the most thrilling matches ever waged between Annapolis and West Point, with 100,000 spectators (including Eleanor Roosevelt) in the stands. By the end of the game, writes Anderson, "the undermanned Cadet players had fought as hard as Vikings, but the Midshipmen prevailed 14-6." Nine days later the US was at war with the Axis, and Anderson's Rockwellian evocations of prewar military life ("Just the name of the naval academy sounded glamorous to him; it conveyed some magical faraway place where everyone was smart and strong") give way to the hard realities of combat in episodes starring four of the game's players, now commissioned officers. Anderson's account of the game itself is first-class, and the lessons to be drawn vis-a-vis football and war will be familiar to anyone who's been inside a locker room: "We were officers in the war," one officer recalls, "but really, we were just kids in our early twenties. But most of us were put in charge of hundreds of soldiers. It's much easier to deal with that kind of responsibility once you've had the experience of playing football in front of 100,000 people." Anderson's war tales are pretty well done, too, though there's a been-there-done-that quality that will make some readers wish he had done a Seabiscuit and stuck to the game and others of its kind during the war years-as he notes, and most interestingly, the 1944 bout alone raised $58 million in war bonds, whilefor other reasons "never in the history of the Army-Navy game had the two service academies played each other with so much on the line." Surely enjoyable for a readership among academy grads and fans of sports history. Of less service as a window onto WWII. Agent: Scott Waxman/Scott Waxman Agency\ \