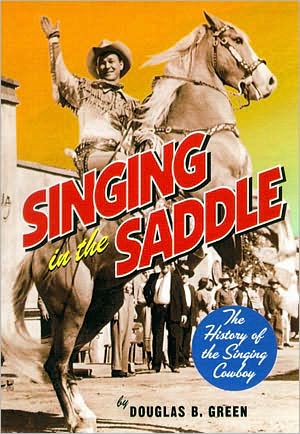

Singing in the Saddle: The History of the Singing Cowboy

As the United States expanded west in the 1800s, and cattle became big business, the figure of the young brash cattleman who rode with the herds quickly emerged as a cultural icon. Victorian Americans went crazy for cowboys, snapping up dime-store novels and sheet music, and turning out in droves for Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. It was only a matter of time before someone brought together these three facets-entertainer, singer, and cowboy. And when Carl T. Sprague recorded the first...

Search in google:

As the United States expanded west in the 1800s, and cattle became big business, the figure of the young brash cattleman who rode with the herds quickly emerged as a cultural icon. Victorian Americans went crazy for cowboys, snapping up dime-store novels and sheet music, and turning out in droves for Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. It was only a matter of time before someone brought together these three facets-entertainer, singer, and cowboy. And when Carl T. Sprague recorded the first hit cowboy record ("When the Work's All Done This Fall") in 1925, the singing cowboy as we know him was born. A singing cowboy himself, Douglas B. Green (better known as Ranger Doug from the Grammy-award-winning group Riders In The Sky) is uniquely suited to write the story of the singing cowboy. He has been collecting information and interviews on western music, films, and performers for nearly thirty years. In this volume, he traces this history from the early days of vaudeville and radio, through the heyday of movie westerns before World War II, to the current revival. He provides rich and careful analysis of the studio system that made men such as Gene Autry and Roy Rogers famous, and he documents the role that country music and regional television stations played in carrying on the singing cowboy tradition after World War II.This book, lavishly illustrated with over 140 photos, is a wealth of information that comes out of decades of research. Green has unearthed never-before-published photos and rare movie posters-including one from an all-Black western, Harlem on the Prairie (1938). Through his close friendships with other singing cowboys and their families, Green is able to provide rare insights into the ways that some like Autry became stars and others like Raoul Walsh (who lost his eye in a shooting accident and later became a famous director) did not.Green also traces the history of cowboy music, from popular songs such as "Sweet Betsy from Pike" to the instantly recognizable harmonies of the Sons of the Pioneers. Green even speculates about just when the famous yodel became a ubiquitous part of the singing cowboy's repertoire. More important, Green reveals how the imagery of the singing cowboy has become such a potent force that even now country musicians don cowboy hats so as to symbolically take part in the legend. Nowhere has the recorded history of the singing cowboy and the film history been collected in one volume, and this book is sure to become the resource for students of the style.Co-published with the Country Music Foundation Press Library Journal These two books explore the Western film genre, which is almost as old as the movie medium itself. In Cowboy, George-Warren (How the West Was Worn) offers a loving, well-illustrated tribute to the Western and its lore, from dime novels to Stetson hats. As the author points out, the connection between the Hollywood Western and reality was often a bit tenuous. Cowgirls, singing cowboys, and matinee idols (including unlikely figures like Cagney and Bogart) may have ruled the box office, but directors like John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Anthony Mann brought mythmaking, spectacle, and hard-edged realism to the genre. Westerns peaked in popularity in the 1950s and 1960s and have rarely appeared since on television or at the multiplex. Cowboy certainly doesn't break any new ground, but George-Warren provides a glimpse of what we have lost, and public library patrons are likely to enjoy the nostalgic text and pictures. Music historian Green, also a member of Western swing group Riders in the Sky, resurrects a nearly forgotten era in his thorough history of the singing cowboy. Singing cowboys were numerous, but only a few, notably Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and Tex Ritter, achieved lasting success. However, as the author notes, even after Hollywood lost interest, singing cowboys influenced country music and regional television. Singing cowboys have enjoyed a modest revival on stage and records in recent years, though it seems the tradition in Hollywood has ridden into the sunset permanently. Cowboy is recommended for all public libraries, while Singing should find a place in large country music and film collections.-Stephen Rees, Levittown Regional Lib., PA Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.

Singing in the Saddle\ The History of the Singing Cowboy\ \ By Douglas B. Green\ The Country Music Foundation Press\ \ Copyright © 2002 Douglas B. Green.\ All rights reserved.\ ISBN: 0-8265-1412-X\ \ \ The Lure of the West\ From the moment more than four hundred years ago that salt-sprayed and weary travelers arrived at the thin crescent of settlement on North America's shores, there was a West beyond the hills, beyond the sunset, a frontier that teased and excited and inflamed the imagination. For a century that West lay just beyond the raw and ragged Appalachians, tantalizing in its promise, unknown in its expanse, frightening in its prospect of cruel and semi-mythical savage man and beast.\ The new nation, once consolidation was achieved, turned its eyes to expansion, and the hero-making process of the bold young United States, still tottering on unsteady legs like a newborn colt, turned from the military heroes of the Revolution to the bold and daring men of the frontier. The new Americans looked to the real and imagined exploits of Daniel Boone forging through the Cumberland Gap, and to the wholly fictional and largely implausible exploits of the first hero of what we might call western fiction, Natty Bumppo—the frontiersman, the deer slayer, the far larger-than-life emblem of the wilderness, the creation of James Fenimore Cooper.\ From the earliest colonial times the settlers had brought with them their music, their books, their love of entertainment. Plays and concerts were common incolonial cities, while on the frontier the fiddle and the human voice were always portable companions for lonely nights. It was inevitable that all these arts, high and low, would eventually reflect the great obsession of the expanding nation: the western frontier.\ Cooper's hero is not unlike many of the fictional westerners we'll meet in the coming pages in that he is slow to anger, wise in the ways of the land, a sure shot, and a peaceable man who rises to moments of great heroism only after extreme provocation, or to help those who cannot help themselves in the environment in which he is master.\ Cooper's ponderous writing style and his ignorance of or willful violation of the laws of man and nature have been deservedly and mercilessly lampooned by Mark Twain and others through the years, but the public, eager to feed its hungry fantasy, willingly forgave errors in writing style, historical accuracy, and physics. It is a willingness the consumer of fiction shares to this day. The popularity of the singing cowboy has waxed and waned, it is true, but it could never have blossomed without this universal urge for novelty, for the romance of the frontier, for heroics beyond the pale of our diurnal lives, for heroes unfettered by the chains of historical accuracy or even of physical possibility.\ Our young nation's insatiable demand for novelty, for fact and fiction portraying the frontier, was responsible for the success of the 1822 stage creation of Noah Ludlow, who wore buckskin and fur cap to sing Samuel Woodworth's song "The Hunters of Kentucky," celebrating the sharp-shooting frontiersmen who helped Andrew Jackson defeat the British in the Battle of New Orleans. Kentucky was, of course, the Wild West of that time, and for a time Daniel Boone and his exploits in opening Kentucky became a focal point of this growing national fascination with the West and its heroes. Historian Henry Nash Smith estimated that Timothy Flint's 1833 biography of Boone was "perhaps the most widely read book about a Western character during the first half of the nineteenth century."\ The frontier was again portrayed notably on stage in the 1831 James Kirke Paulding play titled The Lion of the West. Although the buckskin-clad hero was called Nimrod Wildfire (played to great acclaim by actor James Hackett), it was a clear and obvious portrayal, in sweeping and nearly wholly and wonderfully imaginary details, of the early life of David Crockett, member of the U.S. House of Representatives from the new state of Tennessee. A former scout and half-successful farmer, Crockett had succeeded in politics partly by creating this legend himself, boosting himself as "half-horse, half alligator, and a touch of snapping turtle," as able to "grin the bark off a hickory" as to outtalk and outsmart any opponent, bully, Indian, or politician.\ As a member of Congress, Crockett eventually distanced himself from this hyperbole, but he did come to at least one District of Columbia performance of the play in 1833, where Hackett on the stage and Crockett in the audience bowed to each other to wild applause. Hackett went on to a long career performing the part; it never failed to rouse an audience, especially after Crockett died heroically defending the Alamo in 1836. Crockett's legend only continued to grow after his death, and in 1872 Frank Burdock and Frank Mayo exploited the frontier hero with a play called Davy Crockett; or, Be Sure You're Right, Then Go Ahead, with Mayo in the title role. The play ran for twenty-four years in America and Europe and ceased its run only with Mayo's death in 1896. Indeed, Crockett mania did not end there—some four films, the last a silent version of Burdock and Mayo's play, were released between 1909 and 1916.\ The Davy Crockett Almanac (fictional to the heights of absurdity), volumes of which appeared both before and after Crockett's death, likewise was symptomatic of the eagerness of the public to devour any morsel describing the new frontier. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and Lewis and Clark's celebrated journey of 1805-1807 had already inflamed public interest in the West. The exploits of Jim Bridger and his fellow mountain men were yet another source of great curiosity.\ The public's fascination with the West and the westerner did not focus only on white trailblazers. While the Native American was treated in famously shameful and shabby fashion by the swelling nation, the notion of the "noble savage" emerged as well, and Longfellow's Hiawatha and Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Man," with the lines "Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mind/Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind," were accepted as gospel by a generation of easterners and Europeans, while heartily mocked and scorned in the expanding West. A happier portrayal of the idylls of native life appeared in what we have come to think of as the first popular song written about the West—Marion Dix Sullivan's "Waters of the Blue Juniata," published in 1844:\ Wild roved an Indian maid, Bright Alfarata Where sweep the waters of The Blue Juniata.\ This rollicking tune tells the tale of a happy Indian warrior stoutly plying his canoe "down the rapid river" on his journey to meet his love, the beautiful and bright Alfarata. There is no conflict, no tragedy, no struggle; it is a wilderness portrait of a young man in love, and a beautiful maiden who waits for him at the end of his journey. A love song, pure and simple.\ The Juniata is a lovely stream in western Pennsylvania, which was the West of the time. More important is the song's romanticizing of the West, of life in the West, portraying a land of abundance far from the mad haste of crowded, unhealthy civilization. It is this ideal of the West, couched in song, that meshed so perfectly with the image of the bold frontier hero at home in this land, and that gave us the singing cowboy four score and seven years after "The Blue Juniata."\ The mid-nineteenth-century gold rush to California, Nevada, Colorado, and the Dakota Territory gave enormous fuel to the fires of popular imagination, as thousands pulled up stakes and headed to the land of untold wealth. So did the opening of the Oregon Territory and the tiny caravans of settlers who crossed the enormous emptiness in wagon trains, heading for a land of plenty. Several of the early songs we think of as cowboy, or at least western, came from this period, and some of them have such power that more than a hundred years later they are sung and taught as folklore in our schools: "Betsy from Pike," "Clementine," and "Dreary Black Hills."\ With America's growing population, the rise of high-speed printing (which facilitated sheet music production), and a growing circuit of urban theaters linked by improved roads and railroads, it is not surprising that a burgeoning cadre of songwriters stepped in to fill the need for popular songs. After several years of slavishly imitating British and European models, American songwriters came into their own in the 1840s. Many a love song the cowboys would later sing came from this fertile period, including "Lorena," "Aura Lee," and "Listen to the Mocking Bird."\ America's first fully professional songwriter, Stephen Collins Foster, came of age in that era. He began writing what he called "Ethiopian songs" for minstrel shows, which had come into vogue in the 1840s, though their roots stretched back to a couple of entertainers who appeared on stage in blackface in the 1820s, and to the overwhelming success of Thomas D. Rice, who was a stage sensation with the character and song "Jim Crow." By the early 1850s, Foster had produced many of his most memorable songs: "Old Folks at Home" (1851), "My Old Kentucky Home" (1853), "Old Dog Tray" (1853), "Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair" (1854), and "Hard Times Come Again No More" (1855). Another masterpiece, "Beautiful Dreamer," was published only after his death in 1864.\ It seems bizarre at best and repugnant at least to modern sensibilities to have northern white men, who knew little to nothing of true African-based music, portray plantation slaves with grotesque accents, degrading humor, and simple, catchy songs. However, to the sensibilities of the age, minstrelsy was a sensation, lauded as the most spontaneous, creative, purely American music ever heard—much as jazz would be lauded eighty years later.\ Music also spread to the frontier via tent shows, wagon shows, and showboats, the last a roustabout tradition immortalized by Edna Ferber's 1926 novel Showboat and Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein's 1928 Broadway hit of the same title. There were showboats on the Mississippi as early as 1817, though they hit their heyday in the period following the Civil War. Eventually the rise of the talking film and the ravages of the Depression pretty much put an end to this colorful era of entertainment—which ranged from the plays of Shakespeare and Goethe to fiddle contests, vaudeville artists, and aerial acts, as well as minstrel shows—although remnants plied the rivers of the Midwest as late as 1950. The minstrels were, interestingly, sometimes in blackface and sometimes not; the frontier tended to be more democratic.\ As with Stephen Foster, there was no western content in the dozens of minstrel songs that became popular standards: "I Wish I Was in Dixie's Land," "Old Dan Tucker," "Jordan Am a Hard Road to Travel," "Jim Crack Corn," "Darling Nelly Gray," and of course Foster's "Uncle Ned," "Nelly Bly," and "Oh! Susanna." Yet these songs became national favorites and influenced songwriters to come. The first cowboys of the great trail drives, who were born in this era and grew up with these songs, doubtless sang them and began composing their own songs using them as models.\ There is plenty of evidence that the cowboys' immediate predecessors did so. The young soldiers during the Civil War were accompanied by music in camps and on marches, music that was often martial, played on fife and drum and brass, but that in the evenings was as likely to be popular or folk. It was Robert E. Lee who said in 1864, "I don't believe we can have an army without music," and while he was probably referring to the stirring music of the regimental bands, he could as well have meant the nightly campfire songs that instilled a sense of camaraderie and solidarity among the foot soldiers.\ Pocket-sized songbooks abounded in the war years, with titles like The Soldier Boy's Songster, Beadle's Dime Songs for the War, Hopkins' New Orleans 5 Cent Song-Book, and The Camp Fire Songster. They contained a mix of the folk and the popular: Scottish ballads like "Annie Laurie" (which had also been a favorite with soldiers half a world away during the Crimean War); songs from Thomas Moore's Irish Melodies, such as "'Tis the Last Rose of Summer" and "Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms"; plenty of the Stephen Foster canon; the ubiquitous "Home Sweet Home"; "Lorena"; and songs we associate with the winning of the West—"Clementine," "The Yellow Rose of Texas," and "Betsy from Pike." As the war dragged on, soldiers' favorites included rousing new songs from the popular songwriters of the day—"The Bonnie Blue Flag" in the Confederate camp and "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" and "When Johnny Comes Marching Home" in the Union camp—and less warlike, more sentimental songs as well, such as "All Quiet along the Potomac," "Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!" and "Just before the Battle, Mother."\ At war's end, these were the songs that young men from both sides brought with them as they headed from the exhausted East and ravaged South to the open, beckoning, inviting West. These were the songs the first cowboys and western settlers sang, those young men inured to harsh camp life, used to entertaining themselves with song, familiar with weaponry and skilled in its usage, prepared for hardship and discomfort and danger.\ The movement of many of the heartiest young men to the opening West following the war was simply a continuation of the national fascination with the region. It was seen as the land of unlimited opportunity and unlimited abundance, the place of the future. Soon the cowboy, the driver of cattle on immense open ranges who battled rustler and Native American, became an object of intense curiosity, and he increasingly held sway over the American imagination. He took on myriad contradictory and mythical roles: noble knight, warrior hero, half-wild hooligan, peacemaker, laborer, drink- and gun-happy horseman, and more.\ This heady mixture of truth and fiction was borne eastward to civilization while the West was still new. By 1872 dime-novel writer and noted cowboy popularizer Ned Buntline was appearing onstage with Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro in The Scouts of the Plains. The same year, Dr. Brewster Higley of Smith County, Kansas, published a florid poem that began: "O give me a home where the buffalo roam."\ In 1878 a novel by Thomas Pilgrim (the pseudonym of Arthur Morecamp) called The Live Boys; or, Charlie and Nasho in Texas, was the first to feature the trail drive as a setting. The two juveniles reappeared in a sequel in 1880: The Live Boys in the Black Hills; or, The Young Texas Gold Hunters. In 1882 the Beadle people—the publishers of those five-cent pocket songsters so popular during the Cirri War—brought out Frederick Whittaker's Parson Jim, King of the Cowboys; or, The Gentle Shepherd's Big "Clean Out," the first dime novel to feature a cowboy as its hero. The same year, Buffalo Bill Cody saw a future in presenting his West onstage to a hungry audience and produced a Fourth of July show in North Platte, Nebraska, replete with cowboys, Indians, and an enactment of the Deadwood stage robbery. The following year he brought his show, now called Buffalo Bill's Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition, to the fairgrounds in Omaha, and in 1885, with Annie Oakley and even Chief Sitting Bull added to the spectacle, he called it "The Wild West, or Life among the Red Men and the Road Agents of the Plains and Prairies; An Equine Dramatic Exposition on Grass or under Canvas of the Advantages of Frontiersmen and Cowboys."\ This Wild West exhibition was hugely popular, played all over the world, and toured—in various incarnations with various casts—for some twenty years. Show business had come to, and from, the West while the West was still quite wild, wielding a power over the nation's imagination and pocketbook that continues to this day. There was already the feeling among the public at large that the wild and wonderful western frontier was rapidly disappearing, and that the winning of the West must be lived vicariously through the heroes who tamed it.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ Excerpted from Singing in the Saddle by Douglas B. Green. Copyright © 2002 by Douglas B. Green. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ \

List of Illustrations Acknowledgements Introduction 1. The Lure of the West 2. The Cowboy and Song 3. Western Music in the Air: Record and Radio to 1934 4. The Sons of the Pioneers and Billy Hill: Painting the West in Song 5. Western Music Rides to the Big Screen 6. Gene Autry: Public Cowboy #1 7. The Next Generation: Tex Ritter, Roy Rogers, Dick Foran, Ray Whitley, and the Rest of the Posse 8. Roy Rogers: King of the Cowboys 9. High Noon: The Musical Western at Its Zenith 10. Riding into the Celluloid Sunset 11. In the Ether: Radio, Records, and Television from 1935 12. The Fallow Years 13. Revival Time Line Notes Bibliography

\ From the Publisher\ A lively account of the singing cowboy as both a show-business phenomenon and an icon of American popular culture. \ ---Los Angeles Times Book Review\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThese two books explore the Western film genre, which is almost as old as the movie medium itself. In Cowboy, George-Warren (How the West Was Worn) offers a loving, well-illustrated tribute to the Western and its lore, from dime novels to Stetson hats. As the author points out, the connection between the Hollywood Western and reality was often a bit tenuous. Cowgirls, singing cowboys, and matinee idols (including unlikely figures like Cagney and Bogart) may have ruled the box office, but directors like John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Anthony Mann brought mythmaking, spectacle, and hard-edged realism to the genre. Westerns peaked in popularity in the 1950s and 1960s and have rarely appeared since on television or at the multiplex. Cowboy certainly doesn't break any new ground, but George-Warren provides a glimpse of what we have lost, and public library patrons are likely to enjoy the nostalgic text and pictures. Music historian Green, also a member of Western swing group Riders in the Sky, resurrects a nearly forgotten era in his thorough history of the singing cowboy. Singing cowboys were numerous, but only a few, notably Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and Tex Ritter, achieved lasting success. However, as the author notes, even after Hollywood lost interest, singing cowboys influenced country music and regional television. Singing cowboys have enjoyed a modest revival on stage and records in recent years, though it seems the tradition in Hollywood has ridden into the sunset permanently. Cowboy is recommended for all public libraries, while Singing should find a place in large country music and film collections.-Stephen Rees, Levittown Regional Lib., PA Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \