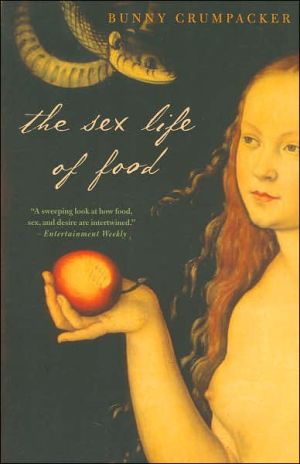

Sex Life of Food

Food and sex. Hunger and the psyche. These are the forces that shape our lives.\ Bunny Crumpacker has looked at food from every angle, and brings us delicious stories about what others have done and said about eating—-and about making love. This is a book you can go back to again and again and keep finding more delights—-including uncharacteristic comments from the famous and insightful chuckles from the author herself.\ It's both a banquet and a late-night nosh. Taste it, devour it, and enjoy!

Search in google:

Food and sex. Hunger and the psyche. These are the forces that shape our lives. Bunny Crumpacker has looked at food from every angle, and brings us delicious stories about what others have done and said about eating—-and about making love. This is a book you can go back to again and again and keep finding more delights—-including uncharacteristic comments from the famous and insightful chuckles from the author herself. It's both a banquet and a late-night nosh. Taste it, devour it, and enjoy!

Chapter One\ Eating Secrets\ My definition of Man is, "a Cooking Animal." The beasts have memory, judgment, and all the faculties and passions of our mind, in a certain degree; but no beast is a cook. . . . Man alone can dress a good dish; and every man whatever is more or less a cook, in seasoning what he himself eats.— Your definition is good, said Mr. Burke, and I now see the full force of the common proverb, "There is reason in the roasting of eggs."\ —The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson, LL.D.,\ by James Boswell\ The first meal is a simple one. Eve's was just a bite of apple; a baby's is just a bit of milk.\ Some babies try to eat even before the first meal: There are infants born with tiny calluses on their thumbs from sucking in utero, already working at filling the void. Once delivered, eating is the first continuing encounter the hungry babe has with the rest of humanity. Food is our first comfort, our first reward. Hunger is our first frustration.\ Simple as it is, that small sip of milk, the first meal is the beginning of a complexity of food and emotion that is mirrored over and over again in a pattern that never stops. When we begin to eat as babies, we fall in love. We discover pleasure, we make friends, we learn to smile. We sup with darker things, too—loneliness and fear, anger, even pain—and relief, after having waited so long, empty, for the next meal.\ No wonder, then, that grown up, when we open our mouths to eat, our souls fly out. We are too thin or too fat. We go on food binges, secret eaters alone with the refrigerator in the middle of the night. We eat too little, and are afraid that too little is too much. We eat too fast and develop heartburn. We work our mouths constantly: We chew gum, we make a fashion of cigars, we drop in for a cup of coffee, we suck on candy, we smoke cigarettes, we talk too much, we drink too much.\ In one way and another, we've been worrying about food since the apes moved down from the trees when the fruit ran out. We've been so busy chewing that we haven't sat down and thought about the missing link between our dinner and our selves, between the way we eat and what we eat and who we are—why we eat in the ways that we do.\ Eating is not a rational process. It is enmeshed in our childhoods, our families, our own personalities. If we were rational, we would eat spiders—juicy tarantulas!—as well as lobsters. We'd eat mice and rats, as well as frogs, snails, and crabs. What we actually do eat is chickens, but not blue jays, rabbits and sheep, but not cats and hamsters. We eat honey, and name it after flowers and ponder the merits of its various flavors. The idea of eating anything produced by a mosquito—or any secretion of any insect—is disgusting to us. But what is honey if it isn't the secretion of an insect?\ Supposedly, human beings eat what is available. But for those of us fortunate enough to live in the lands of plenty, food choices are not limited by the local flora and fauna.* Seasons certainly don't matter anymore: We eat strawberries in December and asparagus year-round. With affluence comes choice. Milk and honey are just the basics. Milk comes in all sorts of ways, most of which are far removed from a cow: You can buy skim milk, homogenized milk, skim milk with milk solids added, lactose-free milk, chocolate milk, organic milk, milk with bacteria taken out, and milk with bacteria put back in. And heavy cream and half-and-half. Ultrapasteurized, sweet, or sour. Honey is available at the corner deli in every flavor, from Greek thyme to killer bee; orange blossom honey is ubiquitous, even though oranges only blossom in warm places. It doesn't matter what grows around here—the peanut butter tree grows everywhere.\ Eating is a very complicated business. Taste is not only a question of what happens to the surface of the tongue when you eat or the number of taste buds that you were born with. It is a cumulative question of judgment, history, and personality jumbled up with smell, texture, sound, sight—and, yes, of course, taste. We think of taste when we think of food, but we forget how important all of our other senses are to our sense of taste (which is the one sense, in many ways, we know the least about).\ Separating taste from everything it is tangled up with is not easy. Texture, for one, is not really taste, but it is certainly related. Crunchiness (the mouth word for noise) can go a long way toward replacing flavor. Crispness is not an attribute of taste; snap, crackle, and pop have no taste at all. Crunchy food makes a lot of noise as we chew it, and taste gets lost in the uproar. Crunch replaces flavor and we are left with nothing but the sound and the fury.\ Sound is also a part of texture, and texture is the feeling of food in the mouth—hard crackers and chewy meats, soft puddings and purees, crisp vegetables, melting chocolate, crunchy nuts. Outer sounds aren't taste, but they are a source of eating pleasure. Think of bacon sizzling and a stew making small bubbling noises as it simmers. These all have to do with expectations of taste and they enhance taste.\ What we see affects what we taste even more than what we hear. In one memorable experiment, a researcher served a panel of tasters six flavors of sherbet. Each serving was normally flavored, but each was without any color. The tasters had a hard time tasting: Flavor is linked to color, both visually and in terms of expectations. Purple tastes grape; lemon tastes yellow.\ It is a cookbook basic that the way food looks affects the way it tastes. Vary the menu, we are told, so that food appeals to the eye before it ever reaches the mouth. Don't serve chicken with cauliflower and mashed potatoes. Too white! Think of cranberry sauce and turkey. They look right.\ Merchandisers have long since adjusted their products to our visual involvement with food. Margarine didn't become a food staple until it was colored yellow. (Somewhere along the line, we stopped calling it oleo except in crossword puzzles. Oleo sounds greasy and cheap; margarine has more dignity.) Even butter often has yellow coloring added to it because butter's natural shade is, to many people, unappetizingly pale.\ Orange juice doesn't seem to taste good unless it's bright orange. Tests have shown that most people don't want to drink yellow orange juice; orange juice with an off taste is all right—even preferred—if it's a nice bright orange. That's how it's supposed to be.\ In 1981, Tropicana donated 26,000 quarts of grapefruit juice to a Florida food bank. The juice had been discolored by an error during production—it wasn't spoiled, or bad; it was just brown and Tropicana knew it would be hard to sell. But even as a give-away, brown grapefruit juice didn't work. "Everybody that drank it said it was good," said a local minister whose church ended up with a thousand cases of the stuff, "but the color was icky." The church was left with the problem of where to dump it.\ We trust hot dogs that have been colored red and Jell-O that is equally tinted, though we've been told the red coloring probably causes cancer. Cancer is a relatively impersonal threat compared with a grayish brown hot dog that we are actually expected to swallow. Same for the nitrites in corned beef, salami, ham—all the cold cuts and preserved meats. Better to deal with cancer tomorrow and have a reddish brown slice of bologna today. Eating is not a rational business.\ Food companies are very aware of the niceties of food color, even on the outside of what they're selling. Packaging colors are most often red and yellow—colors that are cheerful and warm. Black, of course, is pretty much out. White is good, but as we eat—and buy—more natural and organic foods, green and brown are used more often.\ There isn't any difference in taste or nutrition between brown eggs and white ones. Yet people have strong preferences between the two, often with a geographic link. In some parts of America, shoppers prefer brown eggs; in others, white. In recent years, consumers have been buying more brown eggs than they used to, probably as part of the national movement toward eating healthier food. Brown eggs look more natural, and the thinking goes that if they look more natural, they're probably better for you. Before our organic era, in the days when cleanliness was next to godliness, buyers preferred white eggs because they seemed "cleaner," not as much as if they might actually have passed through the body of a chicken.\ All of our senses—sight, sound, smell, and, when we're very young, touch—affect the sense of taste, but more than any of the senses except perhaps smell, taste is affected by relative intangibles—our childhoods, our moods, our personalities, our expectations, even our heritage. Some food is ethnic and reminds us of home and Mother, from pasta to sauerbraten, from pastrami to enchiladas. Food can be male, like sausage, or female, like eggs, or simply get tangled up in our feelings about sex because food and sex are so inextricably linked. Food can be painful and hot, like curry or chili, or soothing and sweet, like custard or turkey in cream sauce. Food can be maternal, like rice pudding, or sexy, like chocolate mousse. Food can be decisive, like broccoli, or just a little vague, like plain mashed potatoes.\ Preferring asparagus to creamed spinach is more than a matter of taste. Asparagus is finger food, and it's biting food, too. Creamed spinach is mushy, very plainly baby food, whether we spoon it in ourselves or have Mommy to help. Spinach is good for you—look at Popeye, another echo of childhood. Asparagus is more sophisticated; you have to know how to eat it. They're both green, but creamed spinach can have a messy, dark look to it; properly cooked asparagus is bright green. Asparagus is a little crisp in the mouth; creamed spinach is smooth and—by definition—creamy. And then there's shape. Creamed spinach has none. Asparagus has plenty; it's the very definition—well, almost—of phallic. Asparagus and spinach are both delicious. Our choice speaks of our mood, our associations, and our memories as well as our taste buds and the rest of today's menu.\ In the years since World War II, the U.S. Army has commissioned three studies of the food likes and dislikes of its soldiers with the goal of giving them what they want. While there have been changes in the results over the years—food tastes have become more adventurous and more ethnic, as the soldiers themselves have—the foods at the top and bottom of the list have been consistent. No one likes stewed prunes. Everyone likes lasagna.\ In the first two studies, clear correlations emerged between the food preferences and education levels of military men and women. In one, soldiers with higher degrees of education put mushrooms, hot tea, grapefruit, crisp relishes, and maple syrup toward the top of the list of foods that they liked. Less well-educated soldiers steered away from all of those choices. The more education a GI had, the less that soldier liked corn flakes, cherry drink, and instant coffee—all of which were preferred by less well-educated GIs.\ To consider these choices in order:\ Copyright © 2006 by Bunny Crumpacker. All rights reserved.

Acknowledgments ixIntroduction xiFilling the Gaps 1Eating Secrets 3The Sex Life of Food 23Eating Styles 33Sex in the Kitchen 41Sex in the Kitchen 43Bedtime Snacks 53Dinner in Bed 63Love and Bread and Wedding Cakes 71A Bun in the Oven 79Growing Up 81Fairy-Tale Food 83I Say It's Spinach-Food Eccentricities and Problems 93Comfort Me With Apples-Comfort Food 107Eating In and Eating Out 119Mine Own Petard-Some Inside Stories 121The Restaurant Democracy 137Chewing the Sound Bite-Political Gastronomy 159Some Eating History 173The Civilizing Process-Manners at the Table 175Immortal Meal-Cannibalism 195Adolph Hitler, Vegetaryan 221The Big Apple 233A Few Relevant Recipes 241Index 249

\ Julie PowellCrumpacker is best when she's idiosyncratic, explaining, for example, that kiwi remind her of "a boy I knew in high school -- just too precious, we all thought, for sex. Not that a kiwi is asexual, exactly, just unsexy, like Billy." Or take this slightly mysterious musing on food as status: "The land of plenty polishes its rice along with its nails and bleaches both its flour and its hair."\ — The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklySensual, comforting and "tangled into every human emotion," food has long evoked love in all its forms, and Crumpacker (The Old-Time Brand-Name Cookbook) explores how our two most raging appetites play upon each other to soothe, satisfy and seduce. Dishing out gobbets of gastronomic history candied with sweet-tart musings, Crumpacker slices into provisions from apples to wedding cake as symbols beyond mere sustenance. In her gloss, both what and how we eat are expressions of the psyche, unremitting quests to fulfill our most primal urges. She takes particular pleasure in teasing out food's more piquant associations (such as "dripping, fleshy mouthfuls" of fruit). Parsing the subtexts of American chow, she considers fast food (wolfed down in bites, it reflects our aggressive, anxious national temperament), ethnic food (oozing with "a rich, fatty kind of love") and salad bars (delighting with array and abundance), and also makes a case for the restorative intimacy of cooking. The obligatory list of aphrodisiacs appears, though Crumpacker debunks their mystique, sticking to her thesis that "we are all beautiful when we are well loved and... well fed." Though seasoned haphazardly with purple prose, Crumpacker's clever insights and lyrical aphorisms blend into an indulgent read. (Feb. 7) Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ Library JournalUsing a clever mix of psychology, physiology, and passion, Crumpacker paints a vivid and utterly fascinating portrait of the role that food plays in people's secret and not-so-secret lives. The author, who wrote two previous cookbooks based on historical recipe pamphlets, uses her own observations as well as a variety of research studies, common sayings, and examples from the arts to weave a rich yarn of the impact food really has. Explaining that food is "tangled into every human emotion," she does an excellent job of showing how food is an expression of personality, neuroses, and psyches. For instance, in Chapter 10, "I Say It's Spinach-Food Eccentricities and Problems," she looks at phobias and the meanings behind refusals to eat certain foods. The title itself is somewhat misleading because Crumpacker covers much more than just the sex life of food! And although she refers to a variety of studies and historical facts and events, she does not include any bibliographical references or suggested readings. Overall, recommended for public and academic libraries.-Lisa A. Ennis, Univ. of Alabama at Birmingham Lib. Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA bubbling stew of food lore, presented with panache and a dash of humor. Crumpacker, a pastry chef and cookbook author, sees food as sexy-e.g., red meat is masculine and so are carrots and bananas; dairy products are feminine, as are oysters and puddings. She finds a deep connection between the way we eat and the way we make love, and she writes joyously of this connection, arguing that if one wants to know what to expect of a prospective lover, he or she should just watch that person eat. Food and sex have been paired from our very beginnings, she says, and cooking can be seen as an act of love; even the smell of food is sexy. However, the food/sex theme occupies only a portion of her book. Almost anything to do with food seems to fascinate her: food eccentricities and phobias, the wide variations across cultures and among individuals in what are perceived as comfort foods, the history of dining out, the atmosphere of fast-food restaurants, the evolution-and decline-of table manners. She also focuses on the role of food in American politics: Herbert Hoover's failed promise to put a chicken in every pot and Gerald Ford's gaffe with a tamale wrapper are but two of the many anecdotes presented. She delights in finding character-revealing traits in Richard Nixon's fondness for cottage cheese with catsup, Ronald Reagan's for jelly beans and Bill Clinton's for virtually everything. Even cannibalism in its various manifestations gets a close look from the author, who provides unexpected information on cooking methods and preferred cuts. For her discussion of vegetarianism, she turns to Hitler, recounting his exceedingly abstemious eating habits and disturbing fears about food, and concludingthat he was as asexual as he was amoral. Crumpacker's zest is boundless, even overwhelming.\ \