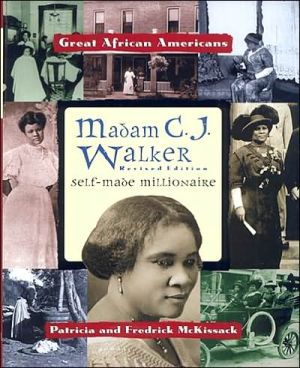

Madam C. J. Walker: Self-Made Millionaire

-- Elementary reading level biographies of inspiring African Americans.\ -- Will satisfy the need for younger biographies written with simple text.\ -- Each book contains a table of contents, a glossary, an index, and comfortably sized type.\ \ Describes the life of the black laundress who founded a cosmetics company and became the first female self-made millionaire in the United States.\

Search in google:

-- Elementary reading level biographies of inspiring African Americans.-- Will satisfy the need for younger biographies written with simple text.-- Each book contains a table of contents, a glossary, an index, and comfortably sized type.School Library JournalGr 3-4-- The lives of entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker and writer Zora Neale Hurston are told in abbreviated form, which gives the basic facts of both women's lives while omitting much of their personality and tenacity. The print is large, open, and easy to read, and the black-and-white photographs and soft pencil sketches extend the texts. Brief glossaries have admirably clear definitions, and the one-page indexes are adequate. Since there are no other biographies of these notables for this age group, they are reasonable acquisitions. However, teachers or librarians may wish to give some verbal background as an introduction. Certainly in Hurston's case, telling one of her stories would say just as much as this biography does about the salty nature of the woman. --Ann Welton, Terminal Park Elementary School, Auburn, WA

Madam C.J. Walker \ Self-Made Millionaire\ \ By Patricia C. McKissack Enslow Publishers \ Copyright © 2001 Patricia C. McKissack\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 9780766016828\ \ \ Introduction \ If Louis XI's inclination to make Tours the permanent capital of France in the 1470s had become a reality, the architectural history of Paris would be very different.1 The gravitation of the Court, its personalities and developing institutions towards Paris, accounts for the building of the great majority of the noble town houses described in these pages. Few of the great or the wealthy who built houses in Paris during the sixteenth century were Parisian by origin or by adoption, and makes the declaration by Frangois I of 1528 that Paris was to become his 'risidence habituelle' or base especially significant.2 The consequences of the King's decision were not immediate, for he did not follow his announcement with any building initiative, but the peripatetic life of the Court had shifted finally from the pleasures of the Loire Valley to the Ile de France where during the second half of his reign Frangois I built at Fontainebleau, Saint Germain en Laye, Villers Cotterets and just west of Paris in the Bois de Boulogne.3 The final confirmation of the King's intention to root his dynasty in Paris came in the 1540s with his rationalization of Royal properties within the walls by selling off for development the large and unwanted Httel de Flandre in the north and the HttelSaint-Pol in the east of the city.4 These and other important lotissements of land belonging to churches within the medieval walls would not have been commercially successful, and have led to rapid and widespread bourgeois and aristocratic building in the late 1540s up to the late 1580s without the King's public and private initiatives. It might be argued that the history of French institutions and of the Church diminishes the significance of the King's action; the Exchequer (Chambre des Comptes) was installed on the Ile de la Citi, the Parlement de Paris had for long been the senior legal and judicial body of the Kingdom and it was only in Paris that each bishop and archbishop kept or had had built a residence.5 Paris was the capital in practice, but the final confirmation of the city's primacy in the realm was the building of the new Louvre, the nexus of monarch and capital. This marriage of the last Valois Kings with Paris was not as immediate nor as decisive as Frangois I's proclamation might lead us to suppose. French Kings to the end of the Ancien Rigime could be circumspect if not hostile towards their capital, but not always as consistently suspicious as Louis XIV. Between his announcement of 1528 and the 1540s Frangois I did nothing more than pull down the keep which filled the greater part of the courtyard of the old Louvre. He said he felt 'at\ \ \ \ home' at Fontainebleau,6 where there was security, comfort and good hunting, and as a result of this preference the Chancellery, Cardinals and some nobles opted to build at Fontainebleau around the chbteau during the 1530s and the early 1540s.7 The form and style of these houses at Fontainebleau have to be considered as a part of the social and architectural history of Paris, as it was the single most significant and active foyer of aristocratic town-house design and building before the shift, apart from helping to fill one of a number of serious gaps in our knowledge of developments in Paris.\ An introduction is not the place to discourage the reader with laments over the large number of important and prestigious lost httels , whose appearance cannot be reconstructed and whose loss defeats any attempt at a representative chronological or stylistic study of domestic architecture in Renaissance Paris. It is more practicable to plot the history of the growth of the city from plans, surveys and the documents of the notarial archives. The reasons for this survey are straightforward. In the modern literature of Renaissance art or architecture Paris is the Cinderella of the European capitals, in which only the Louvre and sometimes the rebuilt Httel Carnavalet and the Httel d'Angouljme make an appearance to represent a hundred years of the city's contribution to architectural style. The process of discovering more of the buildings, their decoration, function and equipment goes on, and more substantial contributions will be produced by French scholars in the years to come, but the fruits of modern research when published are dispersed and little noticed by the non-specialist. Much of the following text is a work of synthesis, which is an attempt to make known a fascinating chapter in architectural history to the English-speaking reader and is a tribute to the work of my friends in Paris.\ London 1982\ \ \ \ 1\ Sebastiano Serlio: Houses for artisans in the Italian and French manner. (Avery ms. n0 XL VIII)\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ Continues... \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Madam C.J. Walker by Patricia C. McKissack Copyright © 2001 by Patricia C. McKissack. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ School Library JournalGr 3-4-- The lives of entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker and writer Zora Neale Hurston are told in abbreviated form, which gives the basic facts of both women's lives while omitting much of their personality and tenacity. The print is large, open, and easy to read, and the black-and-white photographs and soft pencil sketches extend the texts. Brief glossaries have admirably clear definitions, and the one-page indexes are adequate. Since there are no other biographies of these notables for this age group, they are reasonable acquisitions. However, teachers or librarians may wish to give some verbal background as an introduction. Certainly in Hurston's case, telling one of her stories would say just as much as this biography does about the salty nature of the woman. --Ann Welton, Terminal Park Elementary School, Auburn, WA\ \