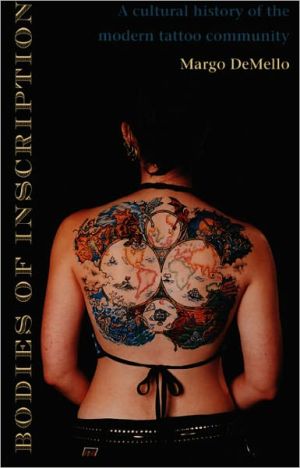

Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community

Since the 1980s, tattooing has emerged anew in the United States as a widely appealing cultural, artistic, and social form. In Bodies of Inscription Margo DeMello explains how elite tattooists, magazine editors, and leaders of tattoo organizations have downplayed the working-class roots of tattooing in order to make it more palatable for middle-class consumption. She shows how a completely new set of meanings derived primarily from non-Western cultures has been created to give tattoos an...

Search in google:

An ethnography of the tattoo community, tracing the practice’s transformation from a mostly male, working-class phenomenon to one adapted and propagated by a more middle-class movement in the period from the 1970s to the present. Library Journal - Chogollah Maroufi An interesting, authentic account of tattoo communities.

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Finding Community\ \ \ Shops, Conventions, Magazines,\ and Cyberspace\ \ \ I don't go to a lot of conventions. They wear me out in a way.\ It's just a mass of people and a sensory overload. I know a lot of\ tattoo artists who work in this town. This is an opportunity for me\ to watch a few artists that I've heard about, and see what they're\ doing, not that I'm planning on simulating it, but it just gives\ me an idea of what people are doing. And in the back of my\ mind, I'm rating them. I got a checklist in my head.\ I am.—Lal M., tattooist\ \ \ One of the central questions of my research involves community. What is it, how is it understood, and how is it realized? Within the group and movement that has come to be known as the tattoo community, the answers to these questions vary according to the position, experience, and motivation of the person being asked, and people's views on the subject will often contradict one another's. My own understanding of community has evolved since I began this study. I first understood it to be a static, place-bound phenomenon found only within tattoo shops. This seemed logical: tattoo shops are where tattooing occurs, thus I felt that community would also occur, or at least originate, there. Later, I realized that the notion of community was not being defined exclusively in the tattoo shop, but was a more fluid notion, one that takes shape in therealm of discourse. I found that community occurs whenever tattooed people talk about themselves, about each other, and to each other —community is a function of that discourse. Therefore, I found community primarily occurring within the pages of magazines and newspapers, in Internet newsgroups, and at tattoo-oriented events across the country. My aim in this chapter is to explore the operation of the tattoo community in the spaces where it is realized (primarily the tattoo convention) and in the texts in which it is defined (magazine and newspaper accounts). This chapter will introduce these sites and will also look at a third site, the Internet, and in particular, at the newsgroup rec.arts.bodyart, which has become for the people who subscribe to it a separate form of community. I will describe the tattoo shop first, because it is the entry point for everyone in the tattoo community. While I maintain that the tattoo convention and media accounts of tattooing are the primary arenas in which community is created, every member of this community begins his or her journey by spending time—often considerable amounts of time—in a tattoo shop.\ \ \ Spending Time in Tattoo Shops\ \ \ A typical tattooist's workday begins at 11:00 or 12:00 in the morning. The tattooist usually begins the day by setting up the workspace: laying out photo albums to display the type of tattoos created in the shop, checking to make sure there are enough supplies (clean needles, bottles of ink, latex gloves), and dealing with money. The tattooist might also sterilize some of yesterday's needles if there was not enough time at the end of the previous evening. The day proceeds as potential customers enter the studio to get tattooed, think about getting tattooed, or just to look at the tattooist's wares. The wares include the posters of flash (sheets depicting tattoo designs) on the walls, design books (filled with images of flowers, animals, "tribal" and "Celtic" designs, and other images used in contemporary tattoos), tattoo magazines, and photographs of the specific tattoos produced in the shop. Depending on the type of shop, some customers will bring their own design, while others will choose one from the flash or design books. Some customers will try to bargain with the tattooist over prices ("I could get my buddy to do this one for a six-pack, man!"), and others will drive the tattooist crazy with questions ("Do they hurt?" "Can I get AIDS from it?" "How much will this one cost? ... OK, well what if I get it a little bit smaller? ... All right, what if I don't get any color, just black? How much then?"). Of course, it's easy for tattooists to take the process of tattooing for granted, but customers anticipating a new (or a first) tattoo are typically very nervous.\ Much of the tattooist's day, even after customers have begun to arrive, is spent not actually giving tattoos but preparing for work (drawing and tracing designs, cleaning equipment, making needle bars, fixing machines, ordering supplies) or talking to potential customers. Actual tattoo work is variable: a tattooist will have days where he or she might only make $40 for a small name tattoo and days where the same tattooist might make $1,500. In my experience, tattooing is not the hardest part of a tattooist's job; instead, it is dealing with customers. At working-class street shops, I have seen drunks come in on a daily basis, customers vomit or faint during a tattoo, and customers challenge and pick fights with the tattooist over prices or an imagined slight. I have also witnessed men and women pulling down their pants or lifting up their shirts to show their homemade tattoo to the tattooist, hoping that perhaps it can be fixed for next to nothing.\ On the other hand, at a custom-only studio frequented by those who want, and can pay for custom tattoos, there are more women coming in with their friends, art students who want to learn how to tattoo, and people who have been thinking about becoming tattooed for, in some cases, months or years, and have finally decided to take the plunge. The tattooists who run these studios do not promote flash-based tattoos; instead, they expect to play a part in designing every tattoo that they create. Their walls, then, are not filled with flash, but are covered with photos and drawings of tattoos created by the artists in the shop, as well as other forms of tattoo-related art, such as comic book art or Japanese art. But not all the customers at a studio like this are middle class and professional. A lot of punks hang out at these shops, as do musicians, artists, and other (often heavily pierced) members of the counterculture. And custom tattooists are not spared the hassles of customer service that often plague the street shop tattooist, even if they don't keep a baseball bat behind the counter for protection.\ In many ways, though, all tattoo shops are alike: the colorful walls, the smell of A&D Ointment, the drill-like sound of the machines, the preponderance of young people hanging out, the nervous laughs of first-time tattoo customers, and the tattooist's emphasis on cash only, no drunks, no minors, and no facial tattoos? Additionally, the process of tattooing is fairly consistent, regardless of the type of shop in which it is performed?\ After the first few years of fieldwork, I no longer spent much time in tattoo shops because the nature of my research changed. But the tattoo shop remains the most important place for the newcomer to learn about tattooing: who gets tattooed, what kinds of tattoos are available, how the process occurs, and what the relationship between artist and customer is. (Of course, it is also the best place to get tattooed.)\ \ \ What Is the Community?\ \ \ Key Rituals * One of my first, and most enduring, research questions has been: How is membership in the tattoo community constituted? I originally thought that the question of membership was personal and that individuals self-identify as members. While individual identification is extremely important, it is my assertion that there are certain key rituals that define membership. These rituals would include first, and obviously, becoming tattooed. (However, having tattoos, even multiple tattoos, does not by itself constitute membership. For example, most sailors or other military men I have spoken to do not consider themselves to be part of a tattoo community and many have never even heard the term. Individuals who have a few tattoos but otherwise show no interest in tattooing would also be excluded.) Second, it is crucial to have enough interest in tattooing to either read tattoo publications (including magazines, books, pamphlets, and calendars), attend tattoo conventions, or both. It is said that tattooing involves a commitment, as the mark made is for life. This is true. But to be a member of the tattoo community requires more than just getting a tattoo—it involves a commitment to learning about tattoos, to meeting other people with tattoos, and to living a lifestyle in which tattoos play an important role.\ Conventions and magazines are important aspects of this commitment for a number of reasons. First, tattoo conventions constitute a space where individuals with a common interest—tattoos —come together for a period of time. While tattoo shops are also places where tattooed individuals congregate, I would argue that a different kind of community is created there. The community surrounding a tattoo shop is more localized and more focused around a particular shop, tattooist, or style of tattoo (for example, a tattoo studio in San Francisco specializing in tribal tattooing will attract a small contingency of punks who identify strongly with that style and what it represents). The sense of community that individuals find in the tattoo convention or reading a tattoo magazine has less to do with the physical congregation of bodies than with a feeling of "shared specialness." Tattooed people define themselves vis-à-vis nontattooed people and the dominant society in general. What makes tattooed people feel they are part of a larger community when attending a convention or reading (and writing to and sending in photographs) a tattoo magazine is a sense that they have found people who are like them and who are not like everyone else.\ The second way that conventions and magazines constitute community has to do with where and how the notion of community is defined within the movement. Without the organized structure of tattoo shows, tattoo magazines, Internet chat groups, and tattoo organizations (which often organize the shows), there would be no broader notion of community, because it is on the pages of tattoo magazines and in the literature promoting tattoo organizations and their shows that a broader idea of a community has taken shape. Before 1976 (when the first big tattoo convention was held), I suggest that the term "community" was unknown among mainstream tattooed people. In addition, while tattooists communicated with each other about the best equipment and supplies, there was also a great deal of competition between tattooists; many were suspicious that other tattooists might gain access to their secrets. One tattooist says of the old days, "There was open hostility between one another, almost. If there was a guy a few hundred miles away or a few thousand miles away, then that's where the communication was. But if they was fairly close, tattoo artists are like dogs—they run around pissin' on each other's territory" (Kenny P., tattooist). Even with the rise of tattoo shows and magazines in the 1970s and 1980s, many older tattooists shunned these new developments, preferring to stay out of the limelight and keep to themselves. Stoney St. Clair, for example, never attended a convention and felt that the public exposure—the "glorification"—was damaging to the profession (St. Clair and Govenar 1981). Another old-timer, Broadway Bill, told me that all the new publicity surrounding tattooing made him suspicious, and he wanted no part in it. On the other hand, there did exist, prior to the development of conventions and magazines, a notion of community among other groups who practiced tattooing—bikers, convicts, sailors, or members of the leather and S/M cultures, for example—but the community was not based on the tattoo, nor did the notion of community extend outside of each specific group to embrace others with tattoos. While the tattoos worn within each group, and especially those worn by convicts and bikers, did serve as important markers of group membership, the communities of bikers, convicts, or leatherboys were based on much more than tattoos. But until the seventies, I can find no evidence—in magazine or newspaper accounts, books on tattooing, or recollections of old-timers—of a notion of community broader than that surrounding a particular shop.\ \ \ But Does It Exist? * My conversations with tattoo convention attendees and the language used on the pages of tattoo magazines indicate that there is, for most, a very clear notion of the tattoo community. This understanding asserts that, in the words of one Los Angeles-based tattooist,\ \ \ It is truly a community in that we recognize that other people who do other styles and types of tattooing, which you may not like or approve of, are all equally as valid. We're actually a family. Most of the tattooers, whatever city they go to, the first thing they'll do is look up the tattooers. Whether you like me or don't like me, you know me because I've been here for twenty-five years.... What does an outsider see of our community? Is the tattoo convention format our community? You know what you really need to do is be in a tattooist's living room, as he's having a beer or doing whatever he's doing, and see the tattooists who are staying in his house that he's never met before, for whom he's opened his doors and allowed them to live in his house, and eat of his refrigerator, and he has no idea who they are. People who I've never met before, who I didn't know existed before, have invited me to share their homes so immediately, they recognize that I share something that they share. Especially when you think you're an island and then this other guy that's doing the same thing, in three seconds you immediately know that that bond is there and that does happen a lot. (Barry B., tattooist)\ \ \ Barry implies that the feeling of community is so strong that tattooists who do not know each other will invite each other to sleep at their homes. For Barry, and others like him, the tattoo community entails communitas, Victor Turner's (1969) term for a feeling of homogeneity, equality, camaraderie, and lack of hierarchy common among those who are marginalized or are undergoing a liminal transition from one state to the next. These assertions about the tattoo community as an example of communitas represent the idealized view of the tattoo community, one that is shared by not only tattoo organizations and tattoo magazine editors but by many members of the tattoo community. The following poem printed in the Tattoo Enthusiast Quarterly (spring 1990) illustrates this feeling.\ \ \ Collectors, fans, masters of the Living Art.\ Like light through a faceted stone.\ Colors reflecting in all directions.\ We come together in a celebration of self—\ Though we are many we are one.\ We share our meaning of life,\ memories past and future dreams.\ All come alive in the artist's hand.\ (Jeri Larsen, "The Bond")\ \ \ The writer's statement "Though we are many we are one" captures the idea of communitas well. By wearing the tattoo (the "Living Art"), the various colors come together "in a celebration of self." It is almost a mystical idea that tattoo collectors achieve a oneness through their tattoos. The process of becoming tattooed includes of course the pain (often ritualized in contemporary accounts) as well as the process of having one's memories and dreams embodied in the tattoo. Thus, this shared process, not to mention the shared marginal status of tattooed people, forms the basis for a near-spiritual union.\ On the other hand, some of the older tattooists I've spoken with dispute this notion of community and would probably find Barry's statement ludicrous that tattooists will invite strangers who are tattooists to sleep on their floors. (For one thing, there are literally thousands of tattooists in this country today, which would make for a lot of very crowded slumber parties.) While the dominant discourse is one of family, equality, and sharing, the reality for these older tattooists also includes stratification, differentiation, and competition. One prominent West Coast tattooist had nothing good to say about the notion of communitas that is so popular among many tattooists and tattoo enthusiasts:\ \ \ I think it's just stupid. It's like saying there's a brotherhood of all tattooed people. There's no commonality in those people. Of course you meet people who you have certain things in common with, but you meet others who you don't have anything in common with.... A lot of them are losers, they're outsiders who don't fit in. By and large, the people that go to conventions ... [are] kind of pathetic if tattooing is the biggest thing in their lives, although I suppose it's no worse than building model airplanes or any other kind of hobby.... I think a lot of them are misfits, you know, and that's okay, but they shouldn't pretend that they're some kind of noble breed. It's [the notion of communitas among tattooed people] a fantasy that they're perpetrating. I think it's great that tattooists can make people feel better about themselves and that they're happy with their tattoos, and that they can get the one that they really want. That's cool. But to make this whole other thing out of it, it's just silly. (Dan P., tattooist)\ \ \ Dan P., a middle-class, educated tattooist, finds the idea of the tattoo conventions representing communitas to be ridiculous for a number of reasons. First, he denies that simply wearing a tattoo gives one a deep connection with others who are tattooed. For this tattooist, tattoos do not have that kind of power. Second, the people who are best represented at tattoo conventions still seem to fit the traditional, biker image, and for Dan P., many are "losers" or "misfits," and not some noble breed. The contradiction between the lofty identity of the tattoo community as a larger brotherhood and the disparities that Dan P. sees among the members strikes him as absurd.\ Both of these views can be seen in the discourses surrounding the two main sites of community: the tattoo convention and the tattoo magazine. The "official" view of communitas is expressed in the literature of the tattoo community, while the critique is found between the lines—in the conflict between members and factions.\ \ \ Tattoo Conventions\ \ \ The tattoo convention is a good example of both communitas and the hierarchy and factionalism that I and others have noted. For many individuals, and certainly for the organizers of these events, tattoo conventions embody a spirit of fellowship and goodwill, as Dan H., a businessman with a Japanese chest-piece, testifies:\ \ \ It's a lot of fun and the conventions are nice because when you become tattooed it's like you become part of the fraternal order or something. It's interesting. Everybody gets along good, it's like a big club. We're all into the same thing, we all admire each other's artwork and all the different styles and the interpretation of the art form. I can walk anywhere in this convention and say, hi, how are you doing, where did you get your work done? ... It's like a private club. And it's neat, you've all gone through the same experience, the anticipation, what am I gonna get, is it gonna hurt and everything, and once you do it, it's an addiction. (Dan H.)\ \ \ For others, however, conventions embody an entirely different spirit:\ \ \ Monkey Business. I mean, that's pretty much accurate. It's a commercial enterprise. People don't come here just to exchange ideas and meet other tattoo artists. They come here to hawk their wares so they can pay for the gas or the car or the plane ticket that brought 'em up here. I mean, these people aren't rock stars or rocket scientists or anything. They're nuts and bolts kind of people from working-class backgrounds. They see an opportunity to make a buck and they're gonna take advantage of it. They come to ... see their old friends and tell some jokes, or whatever. As far as it being a great meeting of the minds or something, you're not going to find a lot of it here. (Paul T., tattooist)\ \ \ Paul, an old-time tattooer, strongly disavows the spiritual/fraternal notion of the community in favor of a starkly materialist interpretation, and from my own perspective, I would say that he gets it just right.\ \ \ Structure * During any given year in the United States, there are approximately five large national conventions and perhaps an additional fifteen or so local shows (in addition to shows all around the Western world). The large events are held at convention centers and hotels and typically run for anywhere from two days to a week, depending on the size of the sponsoring organization. There are also smaller, more exclusive shows, which are usually held for a few hours at a bar or nightclub. The tattoo show (with the exception of smaller, more focused shows such as those exhibiting photos of tattoo art or displaying some aspect of tattoo history) has a threefold structure: it is a commercial event where tattooists and vendors of tattoo-related materials rent booths and sell their products or advertise their services; it is a place where people can enter their tattoos (or tattooists can enter their designs) in contests to be voted on by the general audience or by a panel of judges (usually followed by an awards dinner); and it is a social event, where individuals show off their tattoos and meet other people with the same interests. Sometimes there are additional events, such as piercing demonstrations, dancing, or live music. The National Tattoo Association (NTA) conventions/ as well as the Tattoo Tours, feature seminars on topics such as the history of American tattooing, Marquesan tattooing, Chicano script lettering, portrait drawing, and prevention of transmission of communicable diseases.\ Tattoo conventions, as commercial ventures, are similar to other trade shows held at hotels and convention centers across the country. Vendors rent booths to sell T-shirts, flash, and tattoo-related items, and to give tattoos. The National Tattoo Association regulates activities on the floor of their conventions by limiting tattooing hours and prohibiting the sale of tattoo equipment (machines, needles, or sterilizers), but other conventions are less regulated. Most shows charge from $5 to $20 for admission, with members of the sponsoring organization receiving a discount, and booths typically cost around $200 to rent. Tattoo conventions can be very lucrative: the annual NTA event can gross as much as $200,000.\ \ \ Convention Goers * There are basically two groups of people who attend tattoo conventions. The first are those whose interest in tattooing is strong enough that they are members of the organization that hosted the show. They have registered for the show in advance, have bought a ticket for the length of the show (up to a week), and usually have traveled some distance to get there. Next to attend is the general public, i.e., those who are interested in tattooing but did not register in advance and usually attend for only a day (the conventions are usually open to the general public only on Saturday and Sunday) and live near the convention site. Within this division, however, there is a great deal of variation. Some shows are small and only attract local participants, and some of these shows, due to the geographic location and demographics of the area, primarily attract bikers, the middle-class elite, or younger, avant-garde members. At the NTA shows, I have noticed (just by observation) that of those who register in advance and attend the entire convention, a high percentage are themselves tattooists, and many are working-class tattooists and enthusiasts. On the other hand, the general public who come to the show on the weekend are a more varied crowd and, for the most part, much younger, including punks, more members of the middle class, as well as bikers and tattooists.\ Tattoo conventions also attract eccentric individuals, such as the fifty-five-year-old man who exclusively wears self-executed and handpicked tattoos and takes pictures of other people's tattoos for his "own personal collection." At a convention in San Francisco, I met a man, with no tattoos at all, who went by the name of "Pieface Mike" and made himself available to women to throw pies in his face. He showed me some of his pictures, including one of a bare-chested Annie Sprinkle (a performance artist and porn star) throwing a pie in his face, and said "It's not a requirement that they take their clothes off to pie me, but it helps." When I asked him why he attends tattoo conventions, he said that while he is not tattooed, he feels like a tattooed person because tattooed people enjoy being looked at, and he enjoys being "pied."\ \ \ Contests * Almost every tattoo convention or show includes a contest. The typical contest includes categories for best tattooed male, best tattooed female, best male back, best female back, best black-and-white tattoo, most realistic tattoo, most unique tattoo, and best nostalgic tattoo. Contestants must fill out an entry form for each tattoo (or region of the body) that they want to enter, which includes their name, the name of the tattooist, and a description of the tattoo. The master of ceremonies reads the information as the entrants parade, singly or in groups, across a stage in front of the judges and audience. The participants' descriptions of their tattoos are revealing, and often quite funny, particularly when they are read in the monotone voice of Flo, the elderly secretary of NTA who serves as contest emcee. The following are a few entrants' descriptions of their tattoos:\ \ \ The eradication of the tyranny that is Christianity in this society in the face that is science and nature ...\ A tribal egg with a guy being born out of it, and underneath that, a globe that goes into the armpit with a female figure holding it up with the globe melting and then out of the egg is yolk that goes all around. A rebirth thing ...\ A fantasy scene of a castle with a dragon in the background with the smoke out of his nostrils sweeping down towards a wizard holding a crystal ball ...\ There's a city crumbling into the ocean with an angel flying above it, a space scene behind the angel, with demon faces ...\ A wood elf on a mushroom, with smoke coming from behind it, all leading up to a fantasy scene depicting a wizard throwing fire towards a dragon in the background ...\ \ \ The contests illustrate the hierarchical, competitive notion of community, as contestants are harshly judged on the basis of their tattoos, the appearance of their bodies, and the status of their tattooist. It is ironic that the first tattoo convention was explicitly held in order to foster friendship, communitas, and sharing, yet the contests that have come to dominate the convention are often cutthroat. For this reason, I find watching the contests slightly depressing. Contestants who are clearly proud of their tattoos must parade on a stage and face the ridicule of the watching crowd—often their tattoos (which back home in Ohio seemed innovative, technically superior, or beautiful) are considered out of fashion, inept, or just plain ugly in this highly competitive atmosphere, where tattoos by the elite tattooists almost always win.\ \ \ Modern Day Carnival * The scene at a tattoo convention is carnivalesque. I recorded the following in my field notes at the National Tattoo Convention, San Francisco, March 12, 1994.\ \ \ People who were going to exhibit themselves [in the contest] wore very little. For men, usually just a thong bikini, or sometimes boxers or shorts, depending on the amount of tattoos. For women, sometimes also just a thong bikini, sometimes a bikini top or bra with something sexy or revealing on the bottom, such as a pair of tights with holes cut out to show off the tattoos.... [During the contest] one woman was wearing a Frederick's of Hollywood teddy affair, with violet satiny material down the front and a totally open, string back. The crotch of the teddy was so narrow that you could see part of the woman's shaved genitals. Most of these women's bodies weren't model perfect, or anywhere close, so they were exposing not only their tattoos, but their thighs, bellies, and butts to the world. I was humiliated for them. Another woman came out with a bondage-type outfit, made of black vinyl, with rings and chains and piercings everywhere, on her face and her body. Clearly breaking the rules.... The men were good, too. Most of the men were wearing very little, and many of the men were quite fat, so to see these heavyset, forty-to-fifty-year-old men with just a G-string on was quite amazing.\ One man, on the other hand, was quite attractive with long, soft brown hair. As he was on stage, a woman from the crowd called out, "what's your number," which everyone in the audience interpreted as his entry number. He held that up and she shouted, "No, your phone number!" Everyone laughed. It made me feel like it's not just a meat market for women now, it has become that, to a lesser extent, for men as well.\ (Continues...)\ Swing Swift\ "All-Girl" Bands of the 1940s\ \ \ By Sherrie Tucker\ \ Duke University Press\ Copyright © 2000 Duke University Press. All rights reserved.\

PrefaceAcknowledgementsIntroduction: Bodies and Social Orders11Finding Community: Shops, Conventions, Magazines, and Cyberspace172Cultural Roots: The History of Tattooing in the West443Appropriation and Transformation: The Origins of the Renaissance714Discourse and Differentiation: Media Representation and Tattoo Organizations975The Creation of Meaning I: The New Text1366The Creation of Meaning II: The Tattoo Narratives159Conclusion: The Future of a Movement185Notes195Bibliography207Index219

\ From the Publisher“A fascinating book bursting with penetrating description. DeMello makes a very useful contribution to the literature on these increasingly salient voluntary communities of passion, interest, and identity.”—Gayle Rubin\ “The histories of tattoo traditions presented in this book are fascinating and rich. DeMello has many insights into tattoos’ complexity of meaning, brought out in precise ethnographic and historical fashion.”—Kathleen Stewart, author of A Space on the Side of the Road: Cultural Poetics in an “Other” America\ \ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA respectful look at an aspect of pop culture not normally treated in such unsensational terms.\ \ \ Chogollah MaroufiAn interesting, authentic account of tattoo communities.\ —Library Journal\ \ \ \ \ Patricia MonaghanThis book has much to recommend it for general collections. . . . DeMello’s major interest is in describing the new community of tattooed people, both men and women, for whom new meanings are being forged from the meeting of skin and ink.\ —Booklist\ \ \ \ \ Leo CareyDeMello describes how the new tattoo movement has tried to put a ‘middle class face on the art form.’ Clearly, though, a sense of danger still accounts for much of the tattoo’s allure.\ —The New Yorker\ \ \ \ \ Margot MifflinA penetrating and wonderfully original piece of research, interweaving references to Foucault and Pierre Bourdieu . . . with field work in a well-organized and cleanly written book.\ —The Village Voice\ \ \ \ \ Carol CooperDeMello uncovers some fascinating data about exactly how and why tatoos once associated exclusively with older servicemen and social outlaws have become acceptable for some of today’s brightest young strivers.\ —Honey Magazine\ \ \ \ \ Gayle RubinA fascinating book bursting with penetrating description. DeMello makes a very useful contribution to the literature on these increasingly salient voluntary communities of passion, interest, and identity.\ \